1. Introduction

The Red Sea Arena (RSA), made up of countries surrounding one of the world’s most vital trade routes, possesses vast economic potential that can bring prosperity to its people and make the region a hub for global tourism and commerce. But the RSA is also confronting challenges that could threaten its importance to markets, harm its unique ecological landscape and deepen the region’s income inequality. RSA states – Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Egypt, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Jordan, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Ethiopia – must work together to maintain the region’s security, bolster its relevance in global shipping, diversify its economy and deliver prosperity to its populations.

While the RSA is not a formal union or organisation, its countries share many common security interests as well as numerous longstanding and emerging economic challenges. All have been exposed to increased competition between the United States and China, as Beijing seeks to bolster its regional security footprint and Washington shifts its sights towards the Asia-Pacific. The RSA’s coastal states share a desire to ensure security for vessels navigating the Red Sea, from Bab al-Mandab near Yemen to Egypt’s Suez Canal. But they also have concerns over the emergence of Arctic Sea shipping passages that could pull traffic away from the Red Sea. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which prompted Western sanctions on Moscow and pushed up global energy prices, could drive the European Union and others to direct more sea traffic towards Arctic routes offering shorter and more fuel-efficient Asia-Europe travel times. With climate change reducing ice coverage in the far north, traversing the Northern Sea Route and Canadian Northwest Passage could become year-round possibilities by 2035.

Highlighting changes in Arctic maritime routes due to climate change over the next 30 years

The first step to sustaining the RSA’s economy is for its states to collectively design a cooperation framework for regional development that will ensure security for its trade chokepoints, protect the environment and boost cooperation in project financing, investment, energy and biodiversity. Recent initiatives by Saudi Arabia, which in 2020 helped create the Red Sea Council (RSC) encompassing Arab and African nations, could provide the RSA with a potential framework for cooperation. Riyadh, which has demonstrated a consistent interest in developing the RSA, is well-positioned to take the lead and work together with other wealthy nations like the UAE, Qatar and Turkey to bring new investment to the region through the RSC. The recent gradual rapprochement between Qatar, Turkey and the GCC presents an opportunity to deepen cooperation between the RSC and non-littoral states and bring security, sustainable growth and prosperity to the region’s 253 million population.

2. The RSA’s Strategic Importance

Positioned at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and Africa, the Red Sea has held strategic importance on a global scale throughout history. The waterway connects the Mediterranean to the Arabian Sea and is one of the most-travelled waterways in the world. It offers vessels an 8,900-kilometre (km) shorter shipping route than the most common alternative, South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. The Red Sea is key to facilitating the flow of goods to international markets, with over 1.32 billion tonnes of cargo having transited Bab al-Mandab through the Suez Canal in 2021/2022.1 It is also a vital artery for oil and gas shipments, accounting for 7-10% of the world’s crude and 8% of its liquefied natural gas (LNG) transfers. It further holds importance for agricultural trade, with more than 45 million tonnes of produce passing annually through Bab al-Mandab.

Some 12% of annual global trade transits the Suez Canal, at a value of over $1 trillion. Approximately 1.74 million barrels per day (mbd) of oil transit the Suez Canal,2 along with 25% of Middle East LNG exports bound for European markets. Expansion plans for the canal are underway. Targeting completion in July 2023, Egypt is working to both widen and deepen the canal’s southernmost 30 km and extend a second channel to increase capacity. An incident in 2020 where the Ever Given container ship blocked Suez Canal traffic for six days, preventing the passage of $10 billion worth of daily trade, highlighted the canal’s vulnerability and importance to the global economy.

Cargo vessel making its way through the Red Sea

To the south, the Bab al-Mandab strait is one of the world’s most critical chokepoints, particularly for oil flows. The U.S. Energy Intelligence Administration (EIA) estimates that 6.2 mbd of crude oil and refined products transited the strait in 2018, comprising some 10% of total seaborne-traded oil.3 The strait is perilously narrow, at only 30 km wide, and is divided into two channels by Perim Island. The strait’s proximity to Yemen brings additional security challenges, as regional states fighting in the country’s war try to prevent the Iran-backed Houthi organisation from threatening transiting vessels. The Saudi-led coalition fighting in Yemen constructed what appears to be a military base on Perim Island to counter Houthi threats to maritime trade after a series of attacks on coalition forces. These included explosive-laden remote-control boats targeting the Saudi frigate Al Madinah west of Yemen’s Hodeideh port and numerous incidents involving commercial and naval vessels under the flag of a neutral state.4 In 2018, strikes against two Saudi oil tankers – again near Hodeideh – prompted Saudi to suspend its vessels from crossing Bab al-Mandab. On the strait’s western shores lies Djibouti, which is home to multiple military bases operated by international actors such as China, the U.S., Germany, Spain, Italy, France, the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia. All maintain military presences there to ensure a stake in influencing the security of this key maritime chokepoint.

Alongside its strategic significance, the RSA also possesses a unique ecological environment. The Red Sea is increasingly identified as a potential climate refuge for coral reefs owing to the higher resilience of its corals compared to other parts of the world. The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (RSGA) ecosystem supports biological diversity with a high proportion of endemic species; nearly 15% of Red Sea fish are endemic.5 Fishing provides a main source of food and income for many coastal communities in the region. However, degradation of coastal habitats and overfishing have caused the industry to decline. Furthermore, increased human activity and economic growth have threatened the long-term stability of the Red Sea’s ecosystem while putting pressure on the environment. There can be little doubt that climate change will continue to degrade the Red Sea’s ecosystem. Unless climate change mitigation and adaptation measures are implemented, the Red Sea’s value as a transit route and source of livelihood could be compromised. The combination of coastal erosion, rising waters, acidification and climate events could complicate navigation of the waterway and compromise the efficacy of its ports system while encouraging corporations to move shipping towards the Arctic. Moreover, climate change could accelerate poverty in some RSA states, leading to higher levels of migration, food insecurity and unemployment, thereby fostering instability.

The RSA’s states vary widely in their geography, demography, human capital and natural resource endowments. For example, Egypt’s population reached 106 million in 2022, while Eritrea recorded only 3.6 million. There are also large economic disparities. For instance, Saudi Arabia’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021 was $833.5 billion,6 while Djibouti’s GDP was less than $3.4 billion.7 Yemen ranks 178 out of 189 countries on the Human Development Index8 and as of March 2022, around 17.4 million people in the country require food assistance.9 Excluding Yemen, the western states of the Red Sea face more economic challenges than those of the east and tend to be more prone to periods of poverty. The western states have also experienced prolonged episodes of instability, attributed to economic factors but also to the legacy of colonization.

Many of the RSA’s states take part in other regional organisations and are not necessarily part of groups bound by the Red Sea. For example, Saudi Arabia is more oriented towards the Arabian Gulf and plays a leading role in the GCC. Separately, Egypt is part of the broader Arab world but is also deeply involved in the Egypt-Sudan-Ethiopia water nexus, based around the Nile River and its tributaries.

The RSA’s economy and security environment has been disrupted by the war in Ukraine, demonstrating the widespread effect of the conflict on global energy, trade and food security. The war, along with rising U.S.-China tensions, has led to a reassessment of strategic alliances, both globally and within the Red Sea region itself. Regional players, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Qatar, the UAE and Turkey, are deeply vested in Red Sea security and often project power in the area to protect their interests. For example, Saudi Arabia has increased its focus on the Red Sea’s western shores after the Houthis increased attacks launched in and around the waterway. Competition among regional states has also transformed the RSA, with governments providing political, diplomatic, financial, commercial, military and development support to both state and non-state actors.

The RSA’s importance to global security and market stability has drawn increased attention as Russia’s invasion and shifts in geopolitical alliances help drive up inflation and exacerbate supply chain issues brought on in part by the COVID-19 pandemic. A safe and prosperous RSA can help reinforce stability of global markets, ensure food security and reduce cost of living around the world. Saudi Arabia, through the RSC, must lead efforts to ensure the RSA can take advantage of its unique position in the world and deliver economic success for its populations.

3. Boosting RSA Security to Spur Economic Growth

Given the importance of the Red Sea to global trade and individual countries’ import and export activities, major powers including the U.S., EU, China, and Russia, as well as regional states, share an interest in securing the basin’s maritime integrity and security. Through Saudi-led coordination in the RSC, the RSA can work together to help maintain security in the waterway and spur foreign direct investment by world powers.

Port activity in the RSA

At its core, maritime security is about protecting boundaries and freedom of navigation. In the context of the RSA, the latter is particularly significant. About 90% of global trade is conducted by ocean shipping. Volumes in 2020 measured 10.65 billion tonnes, slightly lower than had been previously forecast because of the pandemic.

Growth is expected to rebound at a compound annual rate of 2.4% from 2022 to 2026.

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), maritime trade volumes are expected to triple by 2050,10 owing to a rapidly expanding e-commerce industry and global population growth. Securing access to critical waterways will remain a high priority for nations and a central feature of national security strategies. This has led many states to project power into the RSA through a variety of means: establishing naval and military bases, lending diplomatic and political support, and providing budget assistance, infrastructure investment, training and development aid.

Maritime security is not restricted to protecting waterways, as it also encompasses protecting against a wider range of threats, such as inter-state conflict, piracy, illegal immigration, human trafficking, weapons and narcotics smuggling, terrorism, illegal fishing and environmental catastrophes. In fact, over the past two decades, maritime security efforts have increasingly been directed towards addressing the impacts of climate change. In many cases – for example, the U.S. Navy’s humanitarian response to Hurricane Matthew in Haiti in 2016 – naval forces deploy as first responders to tackle disasters caused by rising temperatures, sea-level rises and other extreme weather events.

The primary maritime security threats to the RSA emanate from instability in the coastal states. Other threats come from the actions of non-state actors and hostile states seeking to threaten commercial shipping, naval vessels, ports and other coastal infrastructure. Multilateral institutions, including the United Nations and African Union (AU), have thus far contributed over 40,000 military personnel to peacekeeping operations supporting stability in the RSA and Horn of Africa. Individual states have also established military presences in the RSA to secure their own interests, often to ensure the safe flow of commodities through Red Sea chokepoints.

The Red Sea has gained more importance to Asian and European energy security after the U.S. and EU sanctioned Moscow over the Ukraine war, sharply limiting European access to Russian commodities. It is not clear whether the war and sanctions will lead to a structural shift within commodity markets. But with dim prospects for Russia-Ukraine peace negotiations, the current market environment will likely persist for several years. This underlines the RSA’s growing strategic importance to major world powers. It also highlights the urgent need for the RSA to develop a cooperative security arrangement to secure the safe passage of commodities between the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. Below is a breakdown of the strategic security environment surrounding the RSA, and how its states can work together to secure the area for prosperity.

Global Power Competition Could Help Bring New Investment

Key trade and security checkpoints such as Bab al-Mandab and the Suez Canal have drawn increased global attention as the U.S., China, and Russia each seek to expand or adjust their economic, security and political horizons. As Washington recalibrates its security presence in the Middle East and North Africa, both Beijing and Moscow have taken steps to boost their relationships in the region.

Impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine on key trade routes in the region

Competition between the U.S. and China is intensifying as a new international order emerges. China’s access to Africa’s natural resource base depends upon seaborne links to the continent through the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Although the U.S. has not made it a policy priority area, Washington has appointed U.S. Special Envoys to the Horn of Africa in recent years and boosted the scope of work of its military commands in the Middle East and Africa, demonstrating its increased interest in the RSA.

The RSA is a key component of China’s Maritime Silk Road, which sits within its Belt and Road Initiative,11 and Beijing has actively sought to establish a military presence in the region. China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017. It has also made efforts to engrain itself in the development and economies of RSA states, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Sudan, Djibouti and Ethiopia. By providing loans for critical infrastructure in manufacturing, transport, construction, energy and other sectors, Beijing has sought to create an independent trade order that reduces reliance on the Western economic system, enables growth in the Chinese economy and ensures China remains a major global power.

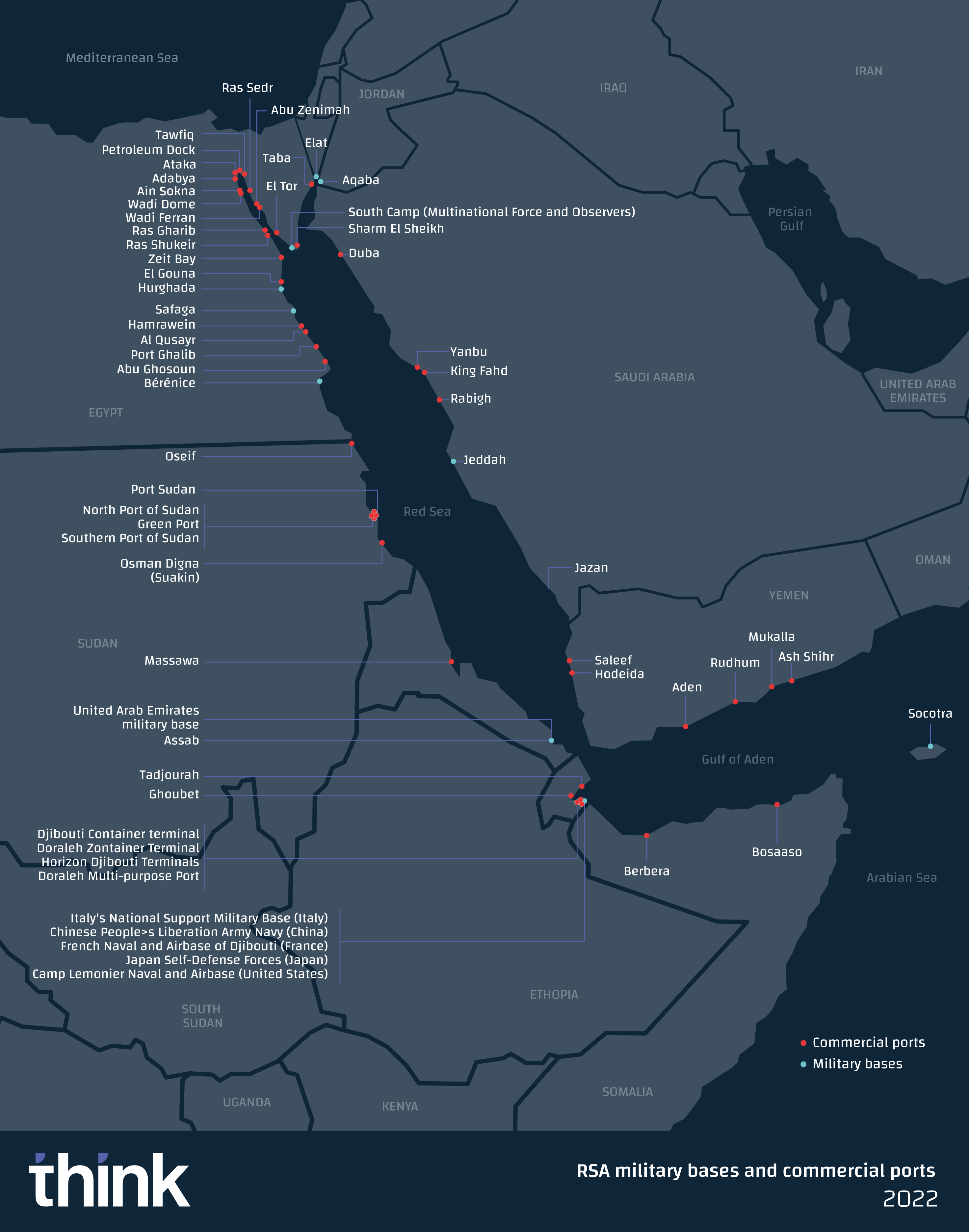

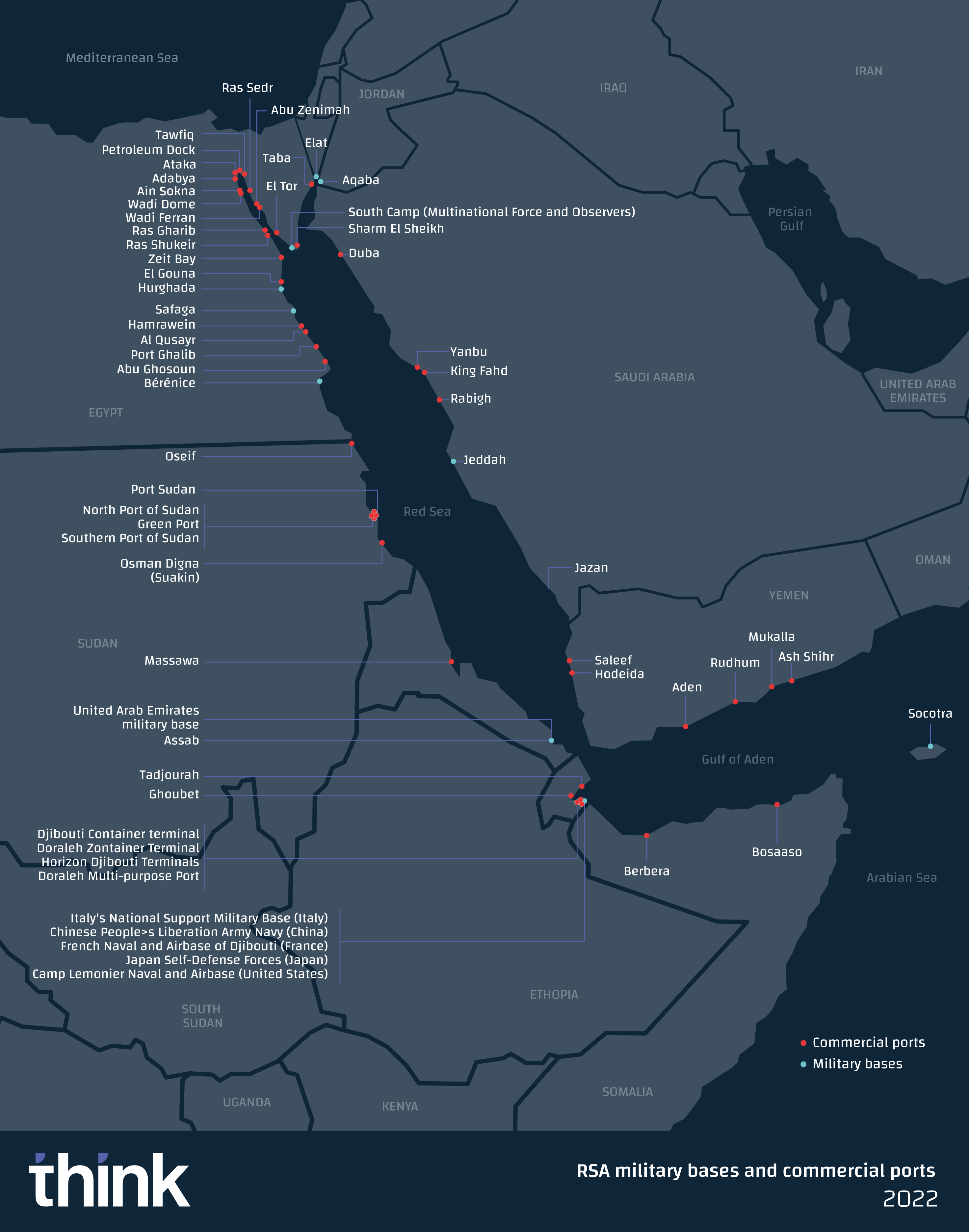

Military bases and commercial ports in RSA littoral states

Thus far, China has been content with the U.S. playing the role of security guarantor in the RSA, benefitting from the stability that Washington’s military presence and political alliances have brought without having to commit its own resources. But while both countries have sought to protect freedom of navigation and security in the Red Sea, they have increasingly focused their regional presences on hedging against each other’s attempts to gain influence in the Middle East and Africa.

For its part, Washington is reassessing its engagement with the Middle East, moving away from the heavy presence bolstered during the Global War on Terror and instead encouraging regional allies to share the collective responsibility of maintaining the area’s security. Historically, the Gulf has played a greater role in Washington’s security calculations, given the onetime importance of Gulf oil to the U.S. market. The U.S. has since practically achieved energy self-sufficiency, though price remains sensitive to global energy markets, while seeking to counter rising threats to and interest in the RSA. With that in mind, Washington has begun to change its thinking about the strategic significance of the RSA, taking steps to ensure it has proper oversight without committing vast military resources. It established a new multinational task force in April 2022, Combined Task Force (CTF) 153. This task force complements previous task forces (CTF 150, 151 and 152) by dividing the geographic area included under the CTF‘s security purview to allow a dedicated task force to cover the Red Sea, Bab al-Mandab and the Gulf of Aden.

While the CTF’s primary focus is Iranian weapons smuggling, particularly to the Houthi movement in Yemen, Russia’s intentions in the RSA will undoubtedly be an area of U.S. concern. Washington has long been concerned with Russian actions in the RSA. The U.S. provided military facilities to Kenya and Somalia in the 1970s to counter Soviet ambition in Africa. Russian influence has once again become a pressing priority, not least because Moscow has already further embedded itself in the Mediterranean through its military support for Syria’s government.

Russia has sought to establish its own naval base in Sudan, although progress has been slow since Omar al-Bashir’s government signed a deal with Moscow in 2017. Under the terms of the agreement, Russia would be given a 25-year lease on a location at Port Sudan. However, the arrangement was paused by Khartoum’s transitional government in 2019. The possible opening of such a base has resurfaced in recent months after Sudan’s military junta seized power in October 2021, a move decried by the U.S. and other international actors, with consequences for Sudan’s foreign economic aid budgets. During a visit to Moscow earlier this year, the deputy head of Sudan’s military junta, General Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, expressed willingness to allow Russia – or any country – to set up a naval base on Sudan’s shores.12 If the deal is reinstated, Moscow would have its first naval base in Africa.

For Russia, Red Sea access is crucial as it is the only year-round maritime link between Europe and its far east.13 As the shortest waterline between its European ports in the Black Sea and the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea is also the quickest route through which Moscow can support its military assets in the region. Establishing a presence in the RSA has long been a priority for Moscow. Russian money and arms flows into East Africa, along with operations by quasi-Russian state security company Wagner Group in countries such as the Central African Republic, demonstrate Moscow’s ambition to bring Africa in as a key partner in a bid to redraw the world order and balance growing influence from other states, namely China.

However, Sudan may well be dangling the possibility of allowing Russia a foothold in this strategically significant arena to encourage the U.S. and others to engage with – and therefore legitimise – its new military leadership, resume aid funding and end Sudan’s international isolation. Sudan’s willingness to take money from and establish close ties with the highest bidder – a practice prevalent in other RSA states as well – undermines the region’s security. Recent reports suggest that internal political divisions in Sudan have stalled talks with Russia yet again. It appears the possibility of alienating the West and other key allies, including Egypt, may be too big a risk to take in the current political climate.14

Taken together, efforts by Beijing and Moscow to boost their relationships in the RSA, and new measures by Washington to maintain its influence, have complicated the regional security landscape. By working together to balance these different relationships, RSA states can help keep the area secure while potentially drawing economic benefits from global powers’ presence in the region.

Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula

Regional States Deepen Engagement as U.S. Shifts Posture

The regional security outlook in the RSA has long been guided by Washington’s security backing for some Red Sea states. Relationships with Washington have become increasingly important to regional governments’ national security strategies, particularly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As Washington shifts its security posture in the RSA, regional powers such as the UAE, Turkey and, to some extent, Egypt have sought to gain influence in the area by boosting their military presences or planning new investments. The RSA can take advantage of this new regional interest by encouraging governments and corporations to boost their investment in the region and offering them a framework through which to act.

Washington has demonstrated its desire to share the security burden in the RSA with regional states through an evolving regional framework. This does not mean that the U.S. will vacate its position as a major security actor. Rather, it will guide, manage and champion the actions of regional partners. In fact, even prior to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the administration of President Joe Biden was already nudging the Middle East towards closer cooperation in the security realm.

CTF 153 is a prime example of Washington’s policy in action. While it demonstrates a U.S. desire to monitor and secure the Red Sea waters, it is also a clear indication of the U.S.’s broader objective regarding regional security. Washington hopes that working more closely with regional navies will allow it to reduce its security provision role while keeping an eye on RSA through resource-efficient practices such as intelligence sharing and analysis.

This shift in U.S. posture has given way to bilateral and multilateral discussions in the region on curtailing Iranian influence that were previously unimaginable. Set against the backdrop of continued Houthi and Iranian malign activities in the RSA, states across the Middle East have embarked on a series of de-escalatory measures. There is now a gradual improvement in relations between Gulf Arab states and Turkey and Qatar. The process of normalization, specifically the Abraham Accords signed between the UAE, Bahrain and Israel, and the staging of the Negev Summit in Israel in March 2022, holds promise for a closer security cooperation framework across both the Gulf and Red Sea.

These shifts have already resulted in additional opportunities for military cooperation, such as joint naval training drills, technology and hardware exchanges and investment and defense agreements. This gives hope that regional states can work together to benefit their collective interests in the RSA. By doing so, they would help stabilize the region and support development while demonstrating to major powers that they have the capacity to manage the RSA’s maritime security environment – making the waterway a safe and viable alternative to Arctic routes.

The economic importance of the RSA’s waters extends beyond its bordering states into the broader region. It is the only sea outlet for Jordan and is the main export route for petroleum sourced from Arab states. The RSA waterways also carry an increasing volume of goods from Israel as Tel Aviv looks to boost its trade with Asian economies. Given the hostility between Israel and Iran and the exercise of Iranian influence via proxy groups in the RSA, securing these exports will be a high priority for Israel. Israel has a naval base at the northern tip of the Red Sea, in Eilat, in part to secure its exports. In July 2022, Israel agreed to the transfer of sovereignty of the Tiran and Sanafir islands – located in the Straits of Tiran, which provide Israel with its only access from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Red Sea – from Egypt to Saudi Arabia. This move signals a changing regional security environment.

For Egypt, the Suez Canal provides the country with one of its top and most reliable sources of national income and foreign currency. Revenues hit a record high of $7 billion in the 2022 financial year to June 30, an increase of 20.7% from the previous year,15 partly due to increases in transit fees implemented to offset the impact of the war in Ukraine. Some of this revenue will be put toward a new investment fund run by the Suez Canal Authority to safeguard the canal from fluctuations in global trade and prevent incidents that could diminish or harm its operating capacity.16

The creation of this new wealth fund continues President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s proactive policy of maximising income from the canal while also boosting its competitive edge against alternative routes. It was this same policy that led the government to borrow from the public – with unprecedented interest rates – to fund the first canal expansion in 2014. Most recently, Danish shipping giant Maersk committed a $500 million investment in the East Port Said terminal. Part of this investment will be focused on making the terminal climate-friendly by 2030, in line with the Suez Canal Authority’s broader plans to make the entire waterway “green” through renewable energy.17

Given the significance of the Suez Canal to Egypt’s economy, Cairo is understandably eager to maintain the channel’s relevance and appeal. Obtaining assistance in securing its surrounding waters plays a key role in achieving that goal. But Cairo also wants to maintain its role as custodian of the canal and is particularly eager to limit the interference of non-littoral states while welcoming investment into its Suez Canal Free Zone. Egypt is also seeking to restrict the influence of Ethiopia given ongoing bilateral tensions over the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project.

The UAE has also established a strategic presence in and along the Red Sea by forging political alliances and building ports and military bases. While Abu Dhabi shares the same set of interests as Saudi Arabia (namely food security, migration, access to new markets, and offsetting Iranian and Turkish influence), it appears to have prioritized stabilizing the RSA in a bid to prepare for and profit from a new China-led international order. The UAE has actively sought to make the RSA its primary commercial shipping route and is working to protect its economic interests therein. Reports emerged in June 2022 of an agreement between Abu Dhabi and Khartoum where the Gulf state would build a new Red Sea port in Sudan as part of a $6 billion package that includes a free trade zone, a major agricultural project and a significant deposit into Sudan’s central bank.18

Turkey has also sought to increase its influence in Africa in recent years. Projecting power in the continent has long been a key element in the foreign policy agenda of President Tayyip Erdogan’s AK Party. Through humanitarian and development projects, economic and business ties and diplomatic and military linkages, Turkey has sought to institute a model of influence in Africa that differs from the US’s security-focused approach and China’s economy-driven framework.19 To this end, Turkey has developed and maintained a strong relationship with Sudan, despite the various political storms in Khartoum over recent years.

Like many others, Turkey has wooed Sudanese leaders through investments in healthcare and education and deals to build a new airport, grain silos, power stations and a free-trade zone in the capital and main port. In 2017, Ankara was permitted by then-president Bashir to assume temporary control of the northeastern Suakin Island, on which it planned to construct a new port. The port would, in part, allow Turkey to benefit financially from religious tourism by providing Muslims in Africa with access to Mecca as well as a naval dock.20 These developments concerned Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the UAE, given Turkey’s close ties to Qatar and support for the Muslim Brotherhood. Turkey’s desire to demonstrate hard power with a physical foothold in the Red Sea adds a complicating dynamic to an already overcrowded and overcharged arena. But the slow rapprochement underway between the Gulf states and Turkey may well enable constructive cooperation, akin to Turkey’s proactive and productive role as a partner in combatting piracy in the Gulf of Aden.

As regional actors attempt to gain new influence in the region, RSA countries must work together to channel this new interest towards broad-based development and new investment. Riyadh can play a key role in shepherding this process, given its strong relations with both global and regional powers.

4. Russia’s Invasion Causes Disruptions, Presents Opportunities

The Red Sea’s importance has grown since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A combination of U.S. and European sanctions on Russia and other major disruptions to both Russian and Ukrainian exports, notably wheat, has led to global supply shortages and exacerbated inflation. Europe’s attempts to make up for the loss of Russian oil and gas will depend in large part on whether it can secure sufficient volumes of crude, refined products and LNG through Bab al-Mandab and the Suez Canal. This highlights the importance of RSA nations joining forces to encourage trade flows through the Red Sea’s arteries and secure investment in the surrounding area.

Russia and Ukraine account for nearly a third of the world’s wheat and a quarter of barley production

The RSA’s role as a key transit node for global energy supplies is becoming increasingly important in the context of current geopolitical and energy market developments. Securing supplies from Gulf oil and gas producers is now of even greater concern in the U.S. and Europe, given the impact of Russia’s invasion on the availability of hydrocarbons. The IEA estimates that following the expected implementation of EU sanctions on Russian oil in December 2022, 2mbd of Russian crude production will be shut in – and therefore off the market for consumers not bound by sanctions, including China and India – by the beginning of 2023.21Consequently, competition for oil will be rife during the northern hemisphere’s winter. Prohibitive natural gas prices will likely compel countries to shift from gas to oil for their power supply due to escalating electricity prices, adding pressure to oil markets.

Oil price volatility will continue as markets respond to an array of signals, including the aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic, threat of global recession, climate negotiations, changing patterns of hydrocarbon investment and the influence of geopolitics. First, supply shortages exacerbated by political turmoil in key producer countries, such as Libya, Iraq and now Russia, have boosted commodity prices, straining the pace of global economic recovery. Second, a revelation that Saudi Arabia’s spare capacity is more conservative than most Western policymakers originally believed has accelerated their drive towards the renewable energy, deterring investment in the hydrocarbon sector.22 Third, geopolitical shocks – the failure of the nuclear negotiations with Iran, and the increased threat of Iranian proxy group attacks on the RSA – will result in a higher risk premium to the cost of crude. Below is a breakdown of the issues at play, and how the RSA can mitigate risks.

As Growth Slows, RSA Can Benefit From Global Supply Chain Shifts

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused widespread market volatility and exacerbated pandemic supply chain disruptions, causing many RSA economies to struggle with inflation and economic slowdowns. But these global challenges could offer potential benefits to the RSA in the form of new investment, as corporations seek to boost growth and avoid supply chain disruptions by emphasizing regional production.

It helps to begin with some background on the global commodity market, followed by a look at how some RSA economies are faring. After hitting record highs in March 2022, commodities plunged to an 18-month low in September 2022 amid growing recession fears. Cumulative outflows have hit a seasonal record of $149 billion year-to-date compared to $122 billion over the same period in 2020.23 As inflation increases across most of the world, the slowdown in growth combined with high unemployment rates – expected to remain above pre-pandemic levels in 2022 – indicate a risk of stagflation to the global economy. From 2021 to 2022, global growth in advanced economies is expected to shrink from 5.7% to 2.9%, with emerging markets and developing economies expected to experience sharper slumps.24 Within the RSA, countries are experiencing the global economic downturn and inflation differently. The latest inflation rates range from 2.7% in Saudi Arabia, 11.6% in Djibouti, 13.6% in Egypt and a staggering 149% in Sudan.

Global supply chains have also come under tremendous pressure, as China’s abrupt lockdowns continue to disrupt manufacturing, shipping and logistics. The lockdowns are reverberating throughout the global economy as China continues to pursue its “Zero Covid” policy, whereby it institutes lockdowns if even just one case is detected in a particular city. This has prompted U.S., European, and Asian powers – and their major corporations – to reconsider their dependencies on distant suppliers and extended supply chains.

One likely consequence of this supply chain shift will be a greater emphasis on regional production and the redirection of investment flows into regional economies, including the RSA. Second, as competition between China and the U.S. intensifies, there is a credible risk that the globalised economy will trend towards fragmentation – and reinforce the shift towards investing in regional economies. Third, new International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulations to better align shipping operations with decarbonization targets will likely lead to the replacement of vessels, reducing the capital available to expand fleets for trade growth. As a result, shipping operators will prioritise shorter, more lucrative routes over longer journeys, putting the Red Sea shipping lanes in direct competition with the Arctic routes. By working together through the RSC, RSA states led by Saudi Arabia can help ensure supply chain shifts lead to more economic activity in the region.

Food Shortages Can Be Addressed Through RSA Collaboration

As supply chain disruptions and inflation persist, the resulting stagflation will likely heighten food insecurity within the RSA and across the globe. The reduction in Russian natural gas inflows to Europe will also contribute to the economic malaise with wide ramifications for food security. A third of European countries are likely to face severe natural gas shortages, and businesses across the continent risk either shutting down or severely limiting operations. This includes critical food-related industries which use natural gas to make products such as fertilizers.

The fertilizer industry is critical to the production and provision of affordable food, helping increase global crop yields. The production of industrial scale fertilizers has revolutionised farming techniques and increased food supplies in the face of massive demand. However, the current energy crisis poses a major threat to food producers’ ability to meet current and future demand. The cost of fertilizer constitutes 35% of a typical farmer’s operating cost for wheat and corn;25 the shortage of available Russian natural gas on the market, and associated price hikes, will compound the wheat shortage crisis and result in sustained price increases for all agricultural products.

The global food crisis in 2007-2008 highlighted vulnerabilities in global and regional food systems, and many of its causal factors apply to today’s crisis: a combination of rising oil prices, commodity shocks, trade disruptions and failures in major crop-producing economies. Climate change and severe droughts also played a key role in the 2007-2008 crisis, a stark warning of what is yet to come.

Wheat imports by origin, in percentage

Food-insecure regions, including Africa and the RSA, will likely experience profound harm. Food insecurity was already a significant problem in the region before the pandemic. In 2020, the Middle East and North Africa, which host 6% of the global population, was home to approximately 20% of food insecure people. Russian and Ukrainian wheat exports make up 25% of global exports. With their contribution now largely off the market, wheat prices in the Middle East have increased a staggering 40% from $300 per tonne in 2021 to a peak of $500 per tonne in spring 2022. 26 Staples such as wheat, rice and lentils are currently at risk of being inaccessible to food-poor communities in Red Sea states.27

Addressing potential wheat and grain shortages has become particularly urgent given the potential for global hunger. Turkey brokered a July deal between Russia and Ukraine that creates a safe corridor for grain vessels coming in and out of Ukrainian ports. But Ukraine’s wheat has still not been reaching its traditional customers in Africa at anywhere close to normal levels. The agreement, which needs to be renewed every four months, expires in November – again raising the threat of a global food crisis, with wide ramifications for RSA states.

Assuming the war in Ukraine and Western sanctions on Russia persist, RSA nations will need to take proactive measures to ensure food security for their populations. Given that wheat makes up a large portion of food consumption in the Middle East, grain shortages are of particular concern to regional countries. Through the RSC, RSA states can conduct a dialogue on how best to address food security challenges and make up for supply shortages.

5. Making RSA An Innovation Leader In Climate, Energy

As the Red Sea grows in importance, the countries surrounding it have become more economically interdependent. This means that economic disruption and instability in one country can harm other RSA states. The risk of economic contagion will likely grow as states such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt further develop their Red Sea economies and widen their dependence on external factors, such as foreign direct investment, technology, international business and tourism. By engaging in consistent dialogue through the RSC, countries in the region can help 1) avoid disruption or instability while ensuring new investment is deployed strategically, rather than simply to mitigate risks in times of crisis, and 2) spur foreign direct investment in innovative fields such as energy and water.

Representatives from the newly formed Red Sea Council (Reuters)

As great power competition in the region intensifies, the RSA’s big powers are already demonstrating a commitment to ensuring their interests are safeguarded and deploying investment strategically. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Arab states have increased their contributions towards the economic development of Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Yemen and Djibouti through instruments including aid, budgetary support and strategic investments. This support helps mitigate the severe repercussions of high inflation, recession and food insecurity faced by the aforementioned countries, thereby reinforcing political stability and the security of the RSA. The Gulf Cooperation Council is also disbursing aid, support and investment to these countries, helping address inflation and a slowdown in growth.

Support lent to Red Sea states will need to become more strategic in its deployment, focusing on areas such as energy diversification, climate change, clean technologies and water desalination. Unlocking the RSA’s economic potential through investment in these areas would lay the foundations of social stability, sustainable growth and development. An economically-developed RSA would be beneficial for regional economies and for global powers seeking to invest in infrastructure along the coast. This can be accomplished with the RSA, through the RSC, playing a supportive role in safeguarding global powers’ interests.

Solar panels and wind turbines present an opportunity for the RSA to pivot towards affordable sustainable electricity production

Diversifying Energy Sources To Meet Demand, Spur Investment

The RSA’s energy-rich states face a major strategic shift given that the long-term outlook for all petroleum-producing economies is negative, as Net Zero targets regain traction. The race for energy diversification has become a key factor shaping future economies, including those in the RSA. Regional countries have various priorities for energy diversification and the deployment of renewable energy. However, one country falling behind on energy targets could destabilize the entire region. There are unsustainable increases in domestic energy demand across all Red Sea littoral states, coupled with low access to electricity in Yemen, Sudan, and Djibouti. Facing this outlook, RSA cooperation and connectivity would render the power systems more efficient. Countries like Saudi Arabia and Egypt are poised to become regional diversification leaders and contribute to technology transfer and project development and financing.

Significant growth in electricity demand is a common problem in RSA countries. Egypt’s annual growth averages slightly less than 4%. Saudi Arabia’s electricity demand growth exceeded 4% in 2021, after several years of decline, due to growth in economic activity. Sudan’s electricity usage has been increasing at 13% annually, even though the country is not fully electrified.28 This growth in demand poses a challenge since regional power generation still depends on fossil fuels, adding pressure to state budgets since electricity from the grid is largely subsidized. For the major petroleum-producers in the region, this also entails lower hydrocarbons volumes for exports and diminished revenues. Energy demand changes and grid connectivity expansion can help bring about more efficient electricity usage.

The global energy crunch further incentivizes the region’s major petroleum producers, such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt, to free hydrocarbons from domestic power generation for export, thus catalyzing commitment to renewable energy. Other countries, such as Sudan and Yemen, are turning towards renewable energy for affordable access to electricity. Their populations suffer from poor access to electricity, which hinders economic development and services provision. For example, in Yemen, 69% of the rural population has access to electricity, compared to 43% in Sudan.29 In Djibouti, only 42% of the entire population has access to power.30 In these three countries, like in other RSA rural areas, a significant share of power is produced by expensive, polluting diesel generators. The cost of this power provision is exorbitant, ranging from $0.50/kilowatt hour (kWh) in non-conflict areas to over $2/kWh,31 with severe disruptions to fuel supply, in areas of conflict. Meanwhile, solar-plus-storage would cost from $0.4 to $1/kWh. The abundance of renewable energy resources in the region, particularly wind and solar, presents an opportunity to pivot from environmentally damaging diesel and provide affordable, sustainable access to electricity while meeting climate targets.

Most of these countries face challenges accessing private financing and have limited state budgets, hindering the deployment of capital-intensive renewable energy systems and energy storage systems. Wealthier RSA nations are thus presented with a unique opportunity to invest in project financing and build the human capital of the least-developed nations around the Red Sea Basin. These investment steps can be coordinated through the RSC, providing the region a vehicle through which to organize its strategic investments.

The Oxagon – one of Saudi Arabia’s key development initiatives

Leading In Climate Change To Protect RSA’s Ecology

Aside from its economic and transport value, the Red Sea is renowned for its distinctive coastal and marine biodiversity. As the region’s tourism appeal grows, so does the threat of climate change. This creates an urgent need for efficient and highly coordinated mitigation and adaptation measures, in addition to oil spill contingency plans and environmentally friendly measures for the shipping industry. RSA states can coordinate climate-focused measures through the RSC.

The region boasts various tourism projects, such as Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Project, NEOM economic zone, Jeddah Central, and Amaala project and Egypt’s El Gouna community.32 All of these projects have green energy and sustainability built into their design. However, rapid economic growth and human activity on the shores of the ecologically sensitive RSA will inevitably have negative consequences for the environment.

One climate hazard can damage the entire region’s ecology. A balance will need to be struck between developing a new, burgeoning sustainable tourism industry – with the important job creation and economic diversification opportunities that delivers – and protecting the environmental sanctity of the ventures’ location.

Frameworks to preserve the Red Sea and neighboring areas have been in place for decades. In 1982, the Jeddah Convention, formerly known as the “Regional Convention for the Conservation of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden Environment”, was signed to protect the two areas from pollution and optimize the management of marine resources.33

A potential spill of oil and other hazardous materials in the Red Sea Basin also constitutes a major and urgent threat. These spills are a frequent problem, given the nature and type of maritime shipping in the region. The FSO Safer, a floating oil storage and offloading vessel moored in the Red Sea north of the Yemeni port of Hodeideh, is only one such example. Citing risk the vessel could spill its 1.1 million barrels of crude oil due to the tanker’s decay, the UN and the IMO are seeking to raise $80 million to mitigate against the environmental and social impact of a spill34, particularly on the RSA’s fishing industries.

Countries around the Red Sea Basin, including Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, and Sudan, have also been partnering with the IMO to implement measures preventing air pollution from ships and promoting energy efficiency in shipping35. These initiatives can offer a guide for future climate change work in the region.

Set New Standards for Clean Technologies, Biofuels

Despite the region’s varying drivers and targets for energy diversification, the RSA, led by Saudi Arabia, has an opportunity to set new standards in clean technologies. This is especially important to increase integration and lower the costs of technologies such as biofuels and energy storage systems.

Saudi Arabia’s landmark Red Sea tourism project plans to operate its facilities through clean technologies, mainly solar photovoltaic, energy storage systems and biofuels. The project is also forecast to host the world’s largest district cooling plant powered by renewables. Some 25 sets of biofuel generators are expected to be implemented with a total production capacity of 112MW.36

Biofuels, produced domestically from waste and organic materials, can displace a share of fossil fuels through a sustainable, renewable source. They can also play a role in responding to growing energy demand and contributing to a circular economy. However, their significant costs have thus far slowed their growth. Government policies and incentives, mainly in the U.S., Europe, India and China, are expected to drive an increase of at least 28% by 2026, compared to 2021 baseline data.37 The deployment of these technologies in the RSA would achieve cost-reduction and transfer of know-how and technology across the entire region.

The same applies for capital intensive energy storage systems (ESS). The Saudi Red Sea tourism project’s planned ESS also sets a new global record as the world’s largest off-grid battery with an energy capacity of 1.2-1.3GWh at a capital cost of $1.3 billion.38

Desalination plants on the coast of the RSA

Beating Drought: Desalination Projects

Countries around the Red Sea Basin are amongst the world’s most water-scarce, providing an opportunity for the RSA, through the RSC, to take steps to bring new desalination investment to the region.

The RSA lacks sufficient fresh water and faces resulting challenges in irrigation, food production and energy security, with increasing regional temperatures making the problem worse. The main source of water – desalination plants – have also been repeatedly subject to attacks, rendering them a major security challenge. Around the Red Sea Basin, many countries must rely on grants to finance desalination projects, while arid but wealthier countries have improved both desalination technologies and financing capacities, enabling them to transfer scientific knowledge and invest in improving regional water resources.

Saudi Arabia is the world’s largest producer of desalinated water and has mastered state-of-the-art technologies. Jordan is turning towards Red Sea desalination to produce 250-300 million cubic meters of potable water annually through a plant in Aqaba, expected to begin operations in 2026. Meanwhile, Egypt is aiming to increase its water desalination capacity by four-fold by 2025. For cash-strapped countries, aid and grants are necessary to build these vital facilities. In Djibouti, the EU financed the $70 million Doraleh desalination plant, the first of its kind in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Yemen, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center inaugurated Hajjah’s two desalination plants.

A Sampling Of Innovative Gulf Investments

The RSA’s strategic location makes it an ideal arena for trade and tourism. However, a tourism breakthrough in the region will require major investment to develop the proper infrastructure, ease passage of tourists and appeal to foreign visitors. Such an effort would also need to include: significant diplomatic engagement between the Red Sea’s coastal states; resolution of conflicts that threaten trade disruption; protection of the passageway from harm to its ecological systems; and deployment of multilateral investment and aid. The RSA’s states can help spur new investment in these areas by creating a framework to address these issues through the RSC.

Gulf states are beginning to act on many of these fronts through the prism of their own national security interests, with a particular focus on investing in the African littoral states. These investments are significant for their political and economic value. For example, Qatar is set to obtain a 17% stake in two of Egypt’s Red Sea oil and gas exploration blocks after inking a deal with Shell in December 2021. This acquisition signals the strengthening of Qatari-Egyptian ties after they re-established diplomatic relations in 2021.

Saudi Arabia, forecast to become the world’s fastest-growing economy this year, is well-positioned to invest in the region’s strategic economic development in the form of infrastructure, construction projects and logistics hubs, among other areas. The Kingdom has set an ambitious agenda to diversify its economy in the form of Vision 2030. Key to achieving this will be safeguarding a stable region, investing in the neighbourhood to underpin broader diversification efforts and exercising regional leadership.

Development initiatives in the Red Sea

The Kingdom had long focused its sights on its eastern shores, where the majority of its oil production sits and to keep an eye on its neighbour Iran. But it has expanded its focus to include its western shores, now considered a strategic priority after the many attacks launched against Saudi territory and interests by the Iranian-backed Houthi movement in Yemen. According to U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen Timothy Lenderking, the Houthis conducted approximately 375 cross-border attacks into Saudi Arabia in 2021 alone.39 The most notable recent attack was March’s drone strikes against several energy facilities in Saudi Arabia’s southern Jizan region and its Red Sea port of Yanbu. The takeover of Sana’a by Houthi forces has prompted a rethink in Riyadh about the strategic significance of its western coast, and the importance of the stability of its African neighbours across the Red Sea. The Kingdom has therefore adjusted its engagement with these African states, seeking to prevent, or at least contain, the potential for conflict and illicit activity. This would minimize risks to the security of the Kingdom’s Red Sea coast and facilities, as well as the waters’ shipping lanes.

Infrastructure has become a major area of focus for Gulf investments, and thereby a means of exerting influence and control. Competition for ports contracts – both construction and operation – is particularly high between states that rely on the Red Sea to transport their exports, including China. In a bid to secure regional interests, a $7.7 billion investment package was signed between Saudi Arabia and Egypt in June 2022, including port management alongside infrastructure development projects. In May, Djibouti invited investors from the Kingdom, including the Public Investment Fund and the Ministry of Industry and Minerals, to invest in ports and logistics projects as part of its international free trade zone, the largest in Africa and a gateway to a continental market of over 1.3 billion people.40

The UAE’s DP World is developing Berbera Port in Somaliland as part of broader plans to make Berbera a major regional trading hub by linking it to Ethiopia via road. The UAE is also building a new port in Sudan to rival the country’s major coastal infrastructure at Port Sudan, at a cost of $4 billion. Qatar is financing a $3 billion redevelopment of Sudan’s historic Red Sea port of Suakin. It is not yet clear how this will affect Turkey’s existing port development project on Suakin, but the close relationship between Ankara and Doha suggests there will be little issue with the projects sitting side by side. In this way, Gulf players are establishing a firm foothold on the African side of the Red Sea. More such investment is needed to bring security and prosperity to the RSA.

6. Bringing RSA Together To Secure The Future

Given that Asian-European maritime traffic will eventually move towards the Arctic, the RSA needs to develop a cooperative ecosystem that can transform the Red Sea region, ensure its security and sustain its economy.

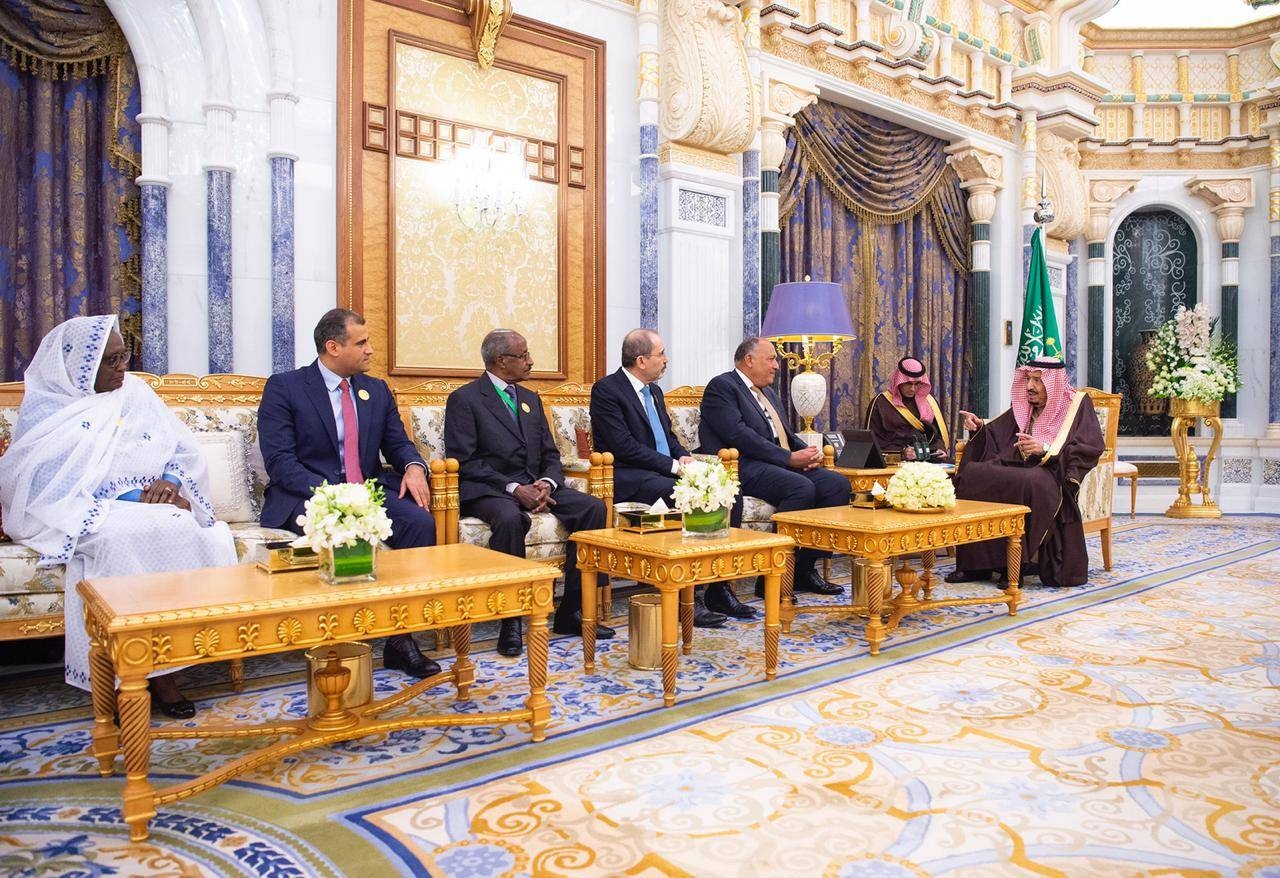

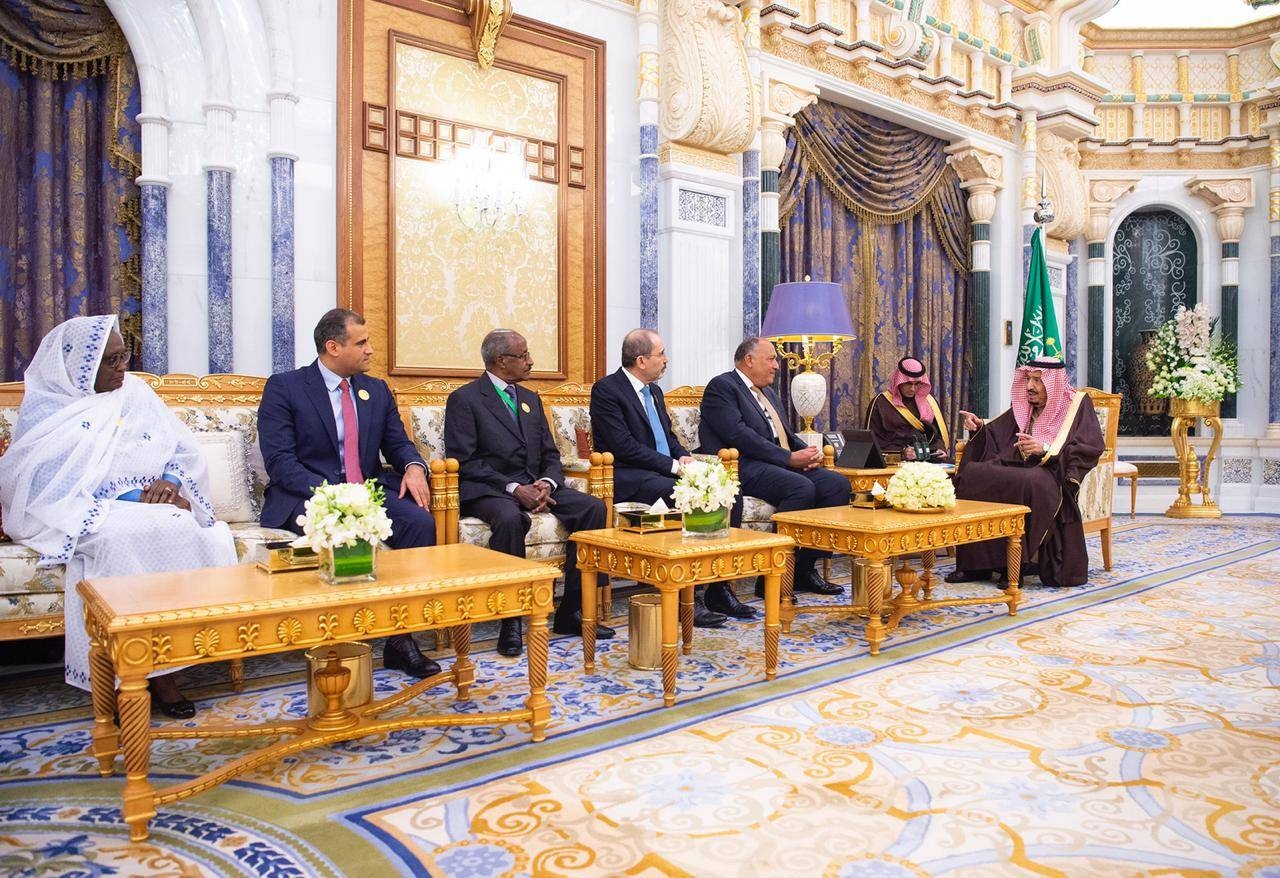

Saudi Arabia’s King Salman received representatives from Red Sea littoral states to discuss joint cooperation (Saudi Press Agency)

Cooperation is in the best interest of all states bordering the Red Sea. There is precedent demonstrating the value of cooperation in the areas of anti-piracy and counterterrorism. Such operations have seen collaboration between a wide range of international stakeholders, including the 34 member states of the CTF. China also responded to piracy issues off the coast of Somalia, dispatching two guided missile destroyers and a supply ship to the Gulf of Aden in 2008. This was notable as it was the first time China engaged in operations outside of its claimed territorial waters41, indicating China’s high priority for the region’s security. The IMO recently stated that after 15 years of dedicated cooperation between military, political, civil society and shipping industry actors, the Indian Ocean is no longer considered at high risk from piracy42. This cooperation has been successful in both eradicating the threat and serving the collective interests of all state actors. Replicating this on a sub-regional scale would be beneficial to RSA states, the region more broadly, and as a result, the world.

Officials floated the idea of a regional organisation to encourage cooperation around the Red Sea as early as 1972. Some organisations were formed, such as the Declaration of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in 1976 and the Jeddah Convention in 1982. After a nearly thirty-year hiatus, in 2020, the foreign ministers of Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen signed a charter creating the Council of Arab and African States Bordering the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, also known as the Red Sea Council (RSC).

The Red Sea Council’s (RSC) primary goal is to enhance regional coordination and cooperation in meeting regional risks and challenges. Closer cooperation amongst member states is intended to reduce the risks to the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden and, therefore, enhance the security and safety of international navigation. Cooperation also mitigates against pervasive terrorist threats and correlated activities, including financial crime, piracy, smuggling, cross-border crime, and illegal immigration.

Although it is highly unlikely that the RSC will develop its own military capability, its formation does suggest that member states will work towards closer security cooperation – in coordination with international partners – and take on a greater share of responsibility for managing Red Sea security. It is not a process that will happen overnight, and it is one that will likely feature significant involvement by Washington, which is intent on helping form a new security framework. The RSC, under the leadership of Saudi Arabia, is the natural vehicle for regional states to play a greater role, not only in the security of the sub-region, but also in helping to insulate it against external shocks, grow local economies and deepen regional development.

The RSC’s objectives also include increasing flows of foreign direct investment and tourism into the region and enhancing stability in the RSA. The recent thaw in relations between the Gulf states, Qatar and Turkey provides a well-timed opportunity to work together through the RSC to secure collective interests in the Red Sea arena. Given that competition for leverage and influence in the arena remains high, major diplomatic efforts are required by both regional players and the international community to prevent conflicts from prevailing over regional needs and aspirations.

Saudi Arabia, as an economically secure and stable nation that is diplomatically engaged with all major world powers, is uniquely positioned to lead this effort. The Kingdom has an incentive to shield the Red Sea from malign actors, especially from political rivals like Iran and Houthi militants, and to develop the RSA as part of its Vision 2030 and national security strategies. Leading a multinational group with complex and sometimes competing interests is not new to the Kingdom. Its role as convenor of the GCC and as de facto leader of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and its extended membership in the form of OPEC+, shows it would find success in managing the Red Sea portfolio.

As a first step in this direction, Riyadh’s creation of and leadership in the RSC signals a clear desire by the Kingdom and the other states to manage great power competition in the RSA while increasing regional states’ own political, economic and security stakes. The RSC would benefit from engaging with a wide range of non-littoral states already invested in the RSA, such as the UAE, Qatar and Turkey. The RSC will be most effective if it can capitalize on the current de-escalatory mood and find common ground on which to cooperate with these key non-member states, especially given their respective presences in the RSA via military bases, ports and investments. Engagement with the broader international community will also be required, given the significance of the Red Sea waters to global trade and the challenges to its primacy in the future.

7. Conclusion

The RSA has long been of global importance, and its significance to international and regional economies has only grown since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing commodity crisis. As long as major powers in Asia and Europe are focused on securing access to the hydrocarbons transiting its waterways, the Sea will remain a vital artery for international trade.

However, in time, trade is likely to move north as importers and exporters alike look for shorter, cheaper and greener alternative shipping routes. This will place pressure on the RSA as it faces a reduction in global hydrocarbons use. But for now, competition to secure and influence the Red Sea and its littoral states – in pursuit of national interests, often by global powers like the U.S. and China – remains high.

As the world braces for an energy crisis, now is the time for the Red Sea littoral states to consider their futures and invest wisely to ensure the Red Sea remains both safe and relevant. Some regional states, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Turkey, have begun to pursue policies in line with this objective. Shifts in regional relationships and the priorities of major powers have created a unique opportunity for even more collaboration in this regard. Cooperation is already increasing between states across the Middle East, creating an ideal foundation on which Red Sea countries can work together to build a secure and sustainable future for the region.

The Red Sea Basin’s ecology must be protected if the region is to have a prosperous future. Investment is needed to bolster regional economies with a focus on forward-looking and energy-efficient economic systems, prioritizing renewables and clean technologies. Lessons learned in cooperation on food and water security should be applied.

Support for the Red Sea region will need to become much more strategic in its deployment, rather than simply serving to avert crises. Unlocking the RSA’s potential for significant growth and development would help mitigate the effects of economic volatility, food insecurity and stagflation, further accelerating sustainable growth. Doing so collaboratively would reduce the risks of localised instability, state failure and, as a result, insecurity contagion.

One climate hazard or catastrophe can harm the entire region. Therefore, a balance will need to be struck between developing burgeoning, sustainable industries – with the important job creation and economic diversification opportunities that delivers – while protecting the very environment that gave rise to them.

Instituting a regionally led and internationally endorsed initiative that encompasses security, economic issues and development is essential to make the RSA prosperous and ensure it remains secure. The RSC, under the leadership of Saudi Arabia, can be the driving force behind protecting, preserving and ensuring the future of this ecologically diverse and economically important arena for the benefit of its people and the world.

References